Category: Uncategorized

Come check out Saint Patrick Press…

I started a publishing company called Saint Patrick Press. It’s mission is to publish books and other materials that are good and true and beautiful.

I’ll be posting regularly to the Saint Patrick Press blog, similar in style and themes that I’ve been (haphazardly) writing here.

We’ve recently published a short novel called Hunger Strike. It’s about a middle aged senior executive who has a major existential meltdown, and decides to go on a hunger strike against his absurd meaningless life and the manufactured world of the ‘American Dream’. But little does he know what the hunger strike will cost him, and what it will take to find himself again …

Feel free to drop by, and check out the books.

I’ll continue to write for Prefaces on topics that may not fit the publishing company; more spontaneous stuff on writing and the creative process.

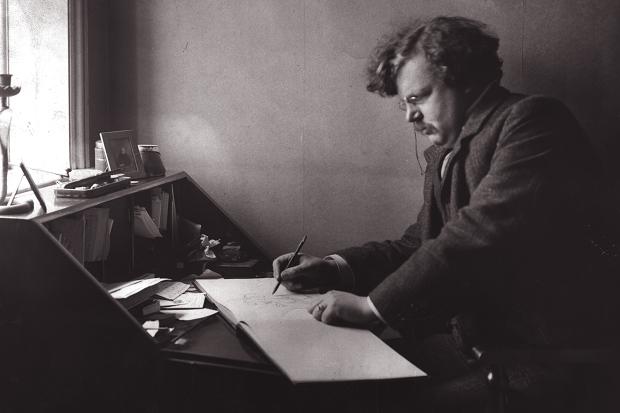

This Is A Simple Three Step Process for Writing

Step 1. It begins with a pen …

When my brother was going through design school, there was a hidden rule that you begin any design process with thumbnail sketches in pencil. Once, he turned in a project that he did entirely on computer–he had skipped the pencil.

The instructor looked at the project and asked, “Did you go right to computer on this one?”

He could tell …

Like any design process that begins with a pencil, to me writing must begin with a pen.

I think better in ink, as if the thoughts are flowing out of my heart, down the bloodstream through my arm, spreading to the hand and flowing out the nib of the pen as ink.

Maybe this is what Hemingway meant that to write one must simply cut a vein and bleed.

The writing must flow first as ink, then undergo typing. Writing fast in ink helps me flow the ideas. I’m not concerned about getting it ‘right’ or pushing out perfectly polished prose. At this stage the writing is just that–writing. And when it’s 6am and I’ve only got 30 minutes to write for the day before heading off to work, I can’t be concerned about polished. All I want to do is get as many words on the page as possible. Don’t judge it, just write it.

Step 2. Typing is really what creates the occasion for reflection.

Preferably I would go to typewriter. I bought one recently and found it really awkward at first. I was so used to little ‘pizza box’ keys on my iPad typepad that I couldn’t handle the full on dexterity needed to type on a manual typewriter. The typewriter is slower and more kinaesthetic, more visceral (‘instinctual, gut, deep down’) than a computer keyboard–you’re literally pounding the words and impressing them into the paper.

The carriage has a finite beginning and end point and must manually be returned to the beginning of the next line. This act of manually moving the carriage back to the next line slows down the process of typing; you must reflect on the writing, find your way back on the page, and continue where you left off when you heard the little bell chime at the end of the line. You need to reflect on the writing while typing it.

Cascading sheets of type …

Another important aspect of the typewriter is the document emerges right away. When you have completed the page, there is an actual material document that is unfurled from the carriage of the machine. It’s so easy to have documents or manuscripts sitting on your desktop somewhere that need to be printed out. I like watching the pages accumulate as I pull them from the carriage, and then the beauty of inserting that new crisp sheet of paper into the typewriter, snapping the page number top centre, hitting the lever a couple of times to get down into the body of the page, then striking those keys again to produce the first word.

Typewriters don’t do Instagram

There is no distraction with the typewriter–you are freely present for the writing, for the words, for the impression of thoughts onto paper. You feel your body while you type–it is an act of intent that goes right down to the tips of the toes.

Once the page is ‘type-set’, you can see the words and how they express the thoughts; you can see the flow of ideas and where there’s congruence and incongruence. And if it’s been typed by typewriter you can see how the ideas are shaping part by part. You can see where large portions of the text hang or fit together or not. You can then edit by pen, going through on a bird’s eye view.

Step 3. Typing the 2nd draft into the computer.

This is like leaving the country roads to the fast lane of the highway. It is a return to the initial vision. It’s like coming home from the mountains along the highway: you’ve seen all you need to see, and want to enjoy the pace of the highway.

Typing on the computer is infinite–it just flows. You’ve done all the hard slow work. This iteration is all about getting another look at the manuscript and by necessity getting it onto a computer where it can be published, sent off to people to proof-read, etc.

The fast work is justified by the slow work that preceded it.

It was Toni Morrison who got me thinking about the process of slowing down. For her, going to computer too early gives you the illusion of writing well: the words are flowing mellifluously and rapidly and they’re all well-formatted which can easily give you the illusion of erudition.

And it was Hemingway who inspired me to consider three eyes on the writing: first, for him, by pencil, second by typing, and third by editing and retyping. There are other writers who have used a version of this approach.

The Art of Slow

The importance for me is working to increasingly slow down. Our world is too fast-paced; technology allows us to speed everything up–even movies. We whip up emails and blog posts in minutes. There’s an importance for all of us writers and artists to master language and communication, and take the time to create well. This may take some less time than others.

I’m not saying this approach is for everyone. But for me, where I want to think deeply and work reflectively, this three part process has been very helpful.

Looking at the work as beginning manually in analogue before going to a digital platform helps you move slowly enough to combat the impact computers and high-speed technology have had on our creative process.

Thus the act of writing, of creating, becomes as it ought to be: reflective and iterative.

Why Writing China Feels Like The Lost Highway

I took a trip to China and left my daily notebook behind. There are two kinds of writers: those who can write away from their work spaces and those who can’t. I read once that Gabriel Garcia Marquez can’t write away from home. I have a hard time writing when I’m away from home too. It’s always a challenge. And I find it hard to write while I’m in the moment of an experience, like on a trip. It’s like I need to filter it all through over time before getting that objective/subjective tension that leads to writing. Photographs don’t help either. For me, I need to be in the moment and then stew on it all for a while and then write about it. It’s like the character in Lost Highway said, something like “I don’t like taking pictures because I like to remember the moment as I experienced it.”

In this trip to China I thought I’d work it into the character of my novel. I had fantasies of ripping through my notebook each evening, or dancing on top of my computer keys at night working all my experiences into my character–didn’t happen. And now that I’m home, it’s still not happening. I don’t know the angle I’d take, and I haven’t had the time to reflect on my trip to see it creatively–it’s still too new and too factual. I don’t want fact–I want poetic fact. I want truth without necessarily being factual, or quantitative or chronological about it.

I still haven’t found my notebook. It’s somewhere. I write in it daily, but haven’t now in almost two weeks. And I’ve dumped this blog for that time too.

But you know, with anything it takes breaking a habit to enter a new one. By writing and publishing this post, I am willing my way back on track.

Now maybe I’ll get around to finding that notebook . . .

This Blog Post Months Later . . .

If I could be the kind of writer that can write phenomena as it happens. If only I could stare out onto a busy street in Chengdu, as pig bladder from that evening’s hotpot stews away in my burning stomach. If I could write how tea is served at meetings, and how it is perfectly polite to slurp while someone is giving a presentation; and how it took me only two days of meetings to become a shameless raving slurper of the finest green tea that has ever passed these lips. If I could write it all as it’s happening—the bamboo groves, the silent workers in green fields, the red lanterns, the thatched huts, the orange trees . . .

But I have a hard time writing like that. Instead, my pen sits in my pocket, or back at the hotel room, and I quietly gaze out of taxi windows, and pray to God that some day I can make sense of it; that someday the experiences will knit together like quilt making patterns and connections in ways I would not have thought while my hand slips out the taxi window and I feel water droplets form along my wrist. To catch phenomena as it happens—to be that kind of writer . . .

I have returned to this blog after a long time away. There is never reason for me to write; nothing burdensome to release onto the pale white surface of the screen—nothing but desire shot through with a sense of duty. To write . . .

A duty to Whom?

I throw words up, and

Let God sort them out—

That’s how it feels some

times it

seems . . .

And China remains

hidden in my unconscious

as time,

nothing but time and

reflection, draws it from

the depths of memory.

A scene from my trip comingles with a story I heard one day on the way to the Rocky Mountains. The story takes place in Japan, but I transport it effortlessly to China; and my soul transmigrates to the protagonist, and he falls prey to a most obscene display of humiliation. And the forlorn buildings at night and the swishing traffic become the backdrop of an encounter with the supernatural—

past experience becomes myth . . .

A favourite movie line comes from David Lynch’s Lost Highway. The protagonist is asked why he does not take pictures. “Because I want to remember things the way I remember them . . .”

That’s the remembering

of a writer.

That’s the writing

of remembering.

On Heidegger And What Writing Truly Is

I write as a habit; to live a habit, a dwelling place, of writing. Habito in the Latin means to dwell. We dwell among our habits. This was a point Heidegger made in, I believe, What is called Thinking? But Heidegger took the habito in Latin and showed how it led etymologically to the ‘bin’ (the ‘ich bin’) of being. Hence to be is to dwell, to inhabit; and thus our habits are ways in which we dwell, and ways in which we are. So to form a habit of writing daily is to dwell in, abide in, writing daily, and thus writing becomes a way of being. Being and doing come together in this act.

But what is the object of writing? For Heidegger, to be human is to be concerned; to dwell in concern. For Paul Tillich, taking Heidegger and pushing him into the transcendent, to be human is to be concerned ultimately about our lives, which is called ‘faith’. And so what is the nature of dwelling in writing? To work out our ultimate concerns. This is called Truth. We seek out Truth as our ultimate concern. And what ultimately are we concerned about? Meaning, purpose, existence, hope, dreams, goodness, justice, mercy. Hence our dwelling in writing is dwelling in what concerns us ultimately and therefore an act of faith, and act of Truth.

But what is dwelling in faith? What is this dwelling, this habit? It is prayer. And thus this habit of writing, this daily dwelling in writing is prayer itself, is worship. A poet and friend of mine Nicholas Samaras says it is presence that makes worship. Writing, as a form of dwelling in attention, is thus worship, is thus prayer. To write in this way is to pray to the orchestrator and finisher of our faith, Jesus Christ–Being Himself, The One Who Is. (This Being of Christ upends Heidegger’s ontic, supplanting it to the mere ontological, a mere study of being without the real authentic experience of Being Itself. It may be the case that Heidegger revised his ontology on his deathbed when the Priest came to receive his confession–we can only hope.) And this is how we dwell in Christ creatively. We dwell in Him through our ultimate concerns that we articulate in our writing, and for which we seek redemption.

And this dwelling in writing, in ultimate concern, in faith, in prayer is authentic creativity. It is connecting our souls to God’s cosmic work, to the work He is doing through all of creation as He is everywhere and filling all things.

And so writing becomes habit, becomes dwelling, becomes faith, becomes prayer, becomes creative dance with God. This is why I am so drawn to writing, drawn to the place of prayer where my concerns are articulated–and not just the negative stuff, but also the beautiful too: to be close to God in prayer, in reflection, in writing. That is what this writing comes to: what concerns me ultimately: who i am, what I am here on this earth to do, and how to do it.

To seek Love, Joy, and Beauty, then dwell in it.

What Stories About Befriending Wild Animals Can Truly Teach Us

There’s a story of a monk who loved animals. He had many dogs and cats in his hut, and in spite of being a rather bullish man, his love of animals seemed to radiate through.

One day he went to a house in the village for a house blessing. As he came through the gates, he was met by the family’s massive German Shepherd that was known throughout the village for being aggressive and vicious. The dog was the size of a small pony! The family stood in shock as the dog ran up to the monk and jumped up on him putting its paws up right on his burly shoulders. The monk just laughed. “Want to wrestle?” he growled at the dog with a chuckle. The dog replied by licking the man’s face. The monk looked toward the stupefied family and laughed. “Aw he’s my friend now! He knows how much I love animals–these dogs are very sensitive, you know!”

There’s something wonderful about these stories of humans encountering and befriending seemingly vicious animals. There’s a teaching here that we can gain insights from about how to become truly human. In the case of the monk, the seemingly vicious dog has an encounter with this man as if it is encountering God; and, it seems, the same can be said about the monk.

Here’s another from a favourite novel of mine, Laurus by Eugene Vodolazkin. The novel traces the spiral-life of Arseny: a physician, nomad, and holy fool. As a young boy, Arseny is taught by his grandfather Christopher the medicinal use of innumerable herbs. One day walking through the forest, young Arseny and his grandfather came upon a wolf.

“Once they saw a wolf while they were gathering plants. The wolf was standing a few steps form them, looking them in the eyes. His tongue dangled from his jaw and trembled from panting. The wold was hot.

“We will not move, said Christopher, and he will leave. O great martyr Georgy, do helpe.

“He will not leave, Arseny objected. He came so he could be with us.

“The boy walked up to the wolf and took him by the scruff. The wolf sat. The end of his tail stuck out from under his hind paws. Christofer leaned against a pine tree and attentively watched Arseny. When they headed for home, the wolf set off after them, his tongue still hanging like a little red flag. The wolf stopped at the border of the village.”

The wolf eventually becomes Arseny’s house pet, lying with him by the fire. There is something magical about this world, something evocative somehow. I will not go into more detail about the wolf without ruining the plot of the story, but the wolf becomes an icon in the book of what icons are supposed to do: bring heaven and earth together.

Arseny’s befriending the wolf, or any stories about monks and wild animals for that matter, is an icon of this real connection humans share with all of creation. And that it’s not the animal’s fault that there exists at times this vicious barrier between it and a human being, but that it is really our fallenness that gets in the way; that if we were actually saints in the true sense of the word, more of these kinds of interactions would be happening. Hence, these stories of wolves and other wild animals are icons of what we all need to become, what we all as humans need to strive and struggle toward by the grace and mercy of God: to become more and more in the image of the One by Whom we were created.

These are the kinds of stories I love; the kinds of stories that reveal how the grace of God can radiate from one so much that even otherwise vicious animals are at peace. Whether it’s the well-known story of St. Francis of Assisi and the wolf, or stories of hermits in the forest who feed bears, these stories show that in Christ we are connected closely to all of creation. “Be at peace with God, and a thousand of others around you will be too,” to awkwardly paraphrase the saying of a desert father.

These stories encourage us to reach beyond ourselves, to reach beyond our fears, our anxieties, our immediacies, our possessions, our mandates, our intellects to something beyond: to tasting heaven here on earth and bringing all of creation along with us.

Dostoevsky And Art As The Pursuit Of Love

There’s something that’s been on my mind–a lot: What is my inspiration for writing? I mean really, what is it that inspires? Where do the ideas come from? What am I trying to get at and why? Fundamental questions, no? Margaret Atwood once said that if you don’t have an idea about what you’re going to write, then you’re probably not a writer. So what is it? And where does it come from?

I wrote in my previous post that my inspiration comes from God through prayer, through worship, through struggling daily to give up my will to Him. Like the prayer of St. Francis, “Lord make me an instrument of your Peace…” This is writing: to be an instrument, a channel, for the Lord. I wrote in that post also that this is where I find my true self, my authentic self, my real self. And this is what art is: to live according to one’s true authentic self. For me, this real authentic self is that which I was created to become; created to become by the hands of God Himself. I am His child, and He lives inside me as He is everywhere filling all things.

But what does this mean? What is the meaning of this prayer that God is everywhere filling all things?

Painting by Ilya Glazunov

Here I turn, as many do, to Dostoevsky–I cannot get enough of him. I’ve been reading his Brothers Karamazov for months now. And as I’ve been on this path of authenticity, of struggling to follow Christ, this book has opened itself to me even more. It is a very spiritual book. But listen, let me show you more.

One of the great characters in the book is the Spiritual Elder Father Zossima. And in that section in which Dostoevsky writes a hagiography of the great elder, Zossima himself tells his life story, the opening of which includes the story of the elder’s brother, Markel. Zossima describes him as one who during Lent “would not fast,” and “was rude and laughed at it.” ‘That’s all silly twaddle and there is no God,’ Markel would say.

One day, Markel became very sick. His mother begged him to go to liturgy, which he did “solely for your sake mother, to please and comfort you.” But his illness worsened, and he took to his bed choosing to take the sacrament at home. He became weaker, and as he did, his faith grew more into a fervent love for all things. Here, read this:

“Don’t cry mother . . . life is paradise, and we are all in paradise, but we won’t see it; if we would we should have heaven on earth the next day.”

And later on Markel would “get up every day, more and more sweet and joyous and full of love.” And the doctor told him he would live many more days and years, to which he replied,

“Why reckon the days? One day is enough for a man to know all happiness. My dear ones, why do we quarrel, try to outshine each other and bear grudges against each other? Let’s go straight into the garden, walk and play there, love, appreciate, and kiss each other, and bless our life.”

Here Dostoevsky is not only painting the picture of the transformation of a man from atheist to Christian, but also painting a picture of the artistic life itself–that authentic way of being in the world. A way of being that doesn’t quarrel or try to outshine another person; a way of being that seeks out creation, and to walk and play and love in it, to appreciate it and love all beings that dwell in it.

But my favourite passage comes a few more lines down in this narrative of Markel. Here, the doctor claims that Markel is dying, but in this slipping into death, we see a kind of resurrection taking place in this young man that culminates in the life of the great elder Zossima. Listen, I shall write it for you.

The windows of his room looked out into the garden, and our garden was a shady one, with old trees in it which were coming into bud. The first birds of spring were flitting in the branches, chirruping and singing at his windows. And looking at them and admiring them, he began suddenly begging their forgiveness, too. “Birds of heaven, happy birds, forgive me, for I have sinned against you too.” That none of us could understand at the time, but he shed tears of joy. “Yes,” he said, “there was God’s glory all about me; birds, trees, meadows, sky, I alone lived in shame and dishonoured it all and did not notice the beauty and the glory”

See this? See this love for all of creation? That is art. That longing for beauty, that longing to be at one with all of creation, to love it, to beg for its forgiveness, to live in harmony with it–that is art.

What is this love? This love that seeks forgiveness from creation; a love that for one moment sees heaven in the eyes of all who walk past. That love that notices the beauty and glory of God in all things. What is this love?

It is a crazy love. It is a thirsty, hungry love. It is not a love of possession or ego. It is a love that springs from the heart when we are quiet, when we are open to God, when we let go of our own plans, our own agendas, our own desires. It is a love that springs from the dance between our gifts and the Giver of them, the Way, Christ Himself. It is a love that struggles to become more and more like God, and thus more and more human.

To live this love; to yearn for it, hunger for it, seek it as the most beautiful treasure, to enter into to, and then to write it–like Dostoevsky did–this, this is art.

The 3 Bridges To Your Next Writing Day After One Has Passed You By

Didn’t write this morning–woke up a bit later than usual (being up in the night with small children can mess with sleep patterns), and had to be out of the house early. I’m not going to worry about it, but simply pick it up again tomorrow morning.

But how will I stay in the momentum of the book having missed this morning’s writing session?

To do this, I utilize a few tricks I’ve picked up along the way over the years of false starts, slothfulness, and self-doubt. Here they are:

Morning Pages

The first is daily pages, which I got from the wonderful book by Julia Cameron entitled The Artist’s Way. If you’re a writer and haven’t read this book, you must. Her book is a kind of program for blocked artists; and one of the ways you unblock is by writing again–through daily pages. This took years for me to learn. I have been an avid note-taker and have innumerable journals throughout the house, but did not develop the discipline of daily writing (hence the name jour-nal).

In order to retrieve your creativity, you need to find it. I ask you to do this by an apparently pointless process I call the morning pages . . . . What are morning pages? Put simply, the morning pages are three pages of longhand writing, strictly stream of consciousness . . . .

– Julia Cameron, The Artist’s Way, 9-10.

Cameron really awakened me to the importance of this discipline, and I’ve been diligently doing my morning pages now for several years. I don’t write in them everyday, I must confess, but most days. Daily pages are particularly useful for working through the book I’m writing, or jotting down ideas from the books I’m reading, or just flickers of insight. So when I miss a day of book writing, I can rely on my daily pages to both keep the ink flowing as well as keep me in the momentum of the book.

Active Notebooking

The second tool is just carrying around a notebook, a small one. Again, I don’t rely on mobile devices because a) I can be a Luddite, in spite of working professionally with technology, and b) I don’t want my intimate ideas being beamed up to a cloud somewhere on a google-barge off the California coast. My notebooks are small. The best kind are slim softcover notebooks. I particularly like ones that Rhodia puts out: they’re very slim and the paper is very kind to fountain pens. These notebooks can fit seamlessly in my denim or blazer pockets. And when an idea hits, I jot them down immediately, being sure to date the pages. I will go later into my system of notebooks and note taking, but am just mentioning it broadly here.

Beating Resistance

One of my mentors–though he doesn’t know it, for I’ve never (yet) met him–is Steven Pressfield. In his book The War of Art, Preston pinpoints the most destructive force that every artist faces: Resistance. There are many ways we fall prey to resistance, but only one way to beat it: work–plain and simply. Just sit down and write. The hardest thing for any writer is simply sit down. The hardest part for me is the moment my alarm goes off at some crude hour of the morning and I am left with the fateful decision: get up and go downstairs to write, or drift back to sleep. If (a) I will be successful for the day; but if I choose (b) Resistance has defeated me.

[Joseph] Conrad, who could spend days looking at a blank page, didn’t start writing fiction until his thirties. Nevertheless, he averaged a book or play a year until his death at age sixty-six . . . . Only a few of Conrad’s pieces are masterpieces, but the ones that are didn’t come from a mere few years’ inspiration; they came from Conrad’s ability and willingness to dedicate nearly his whole existence to his creative activity.

– John Briggs, Fire in the Crucible pg. 204.

So this third trick of mine has a bit of a crude name: Sitzfleisch, which is German for ‘sitting down flesh’. The trick is to commit to sitting down everyday to write, unless another commitment takes you away. Some writers write 7 days a week. I write 5-6 days a week, taking Sunday off (but still keeping my active note taking). When I am committed to writing everyday, it doesn’t matter if I miss one, because I know that tomorrow morning my alarm will go off, and I’ll stagger downstairs, set up my workspace, and get down to business continuing where I left off and using my notebook(s) as a bridge.

The Singularity or Everlasting Life?

For a number of years now I have thought a lot about longevity: I’ve read Ray Kurzweil’s books and regaled myself with Aubrey de Grey’s various talks on TED etc. “Would I chip, or not chip?” has been a lingering nagging question, the weight of which brought on by Bill Gates and others who warn us that if we do not enhance our brains technologically we risk being conquered by ever and rapidly advancing artificial intelligence. If Ray Kurzweil is right, we’ll want to enhance our brains through ‘chipping’ not only to avoid intellectual but also existential obsolescence.

I’ve asked myself so many times, “What’s my longevity plan?” It’s a big issue. As we’re moving closer toward singularity, I have had innumerable conversations with people about the importance of enhancing our brains–I’ve even consulted people in such directions for business plans and other strategic points of departure.

Aren’t we geared toward thinking of our future? Isn’t that a primordial, fundamental human concern? What will happen tomorrow? Will I live or will I die? Will I have enough? Will I grow ill and be unable to recover? What happens in the moment of a catastrophe? Am I ready?

Biotechnological solutions are ways for us to insure a future for ourselves; to shore up against age, disease, dementia, and even career obsolescence.

And what about from a Christian perspective, for those who are? Would you chip? What does it mean to take it? To what are you wired up? Whose controlling whom? And even outside of the Christian context, what about basic human liberty–are you free if you take a chip?

“Yes–” one would argue, “but look at the benefits! Living for the next 300 years with an amped up brain capacity that would make Einstein look feeble! Who doesn’t want that? Besides, computers and all external forms of data gathering, are passe, not to mention onerous.”

It wasn’t until I sat in the Pascal Lectures by John Lennox that I came to a crazy realization that I have been taught since Sunday school, but in the course of ‘becoming educated’ withdrew from consciousness: That as a Christian, a believer in Christ, I have everlasting life. What does this mean?

In the story of Genesis, we see human beings with these amazing bodies and minds: supple, youthful bodies, and minds one-pointed and straight-edged. But at the fall, everything changed: our bodies became degenerative, and our minds divided. When Christ came, he revealed to us not only that He is God (in the beginning was the Word), and not only that He suffers with us, but most importantly that He defeated death through His resurrection.

In the book of John, Jesus appears to Mary, Martha, and the disciples. Did they recognize Him at first? No. In fact, He chose to reveal Himself to them, after which they recognized Him. John tells us that His body was so magnificent, so glorious, that He was unrecognizable–even by His closest friends and mother. And through His resurrected body, Christ shows us what our bodies will be like in Eternity–unrecognizable, and like the bodies of the first humans prior to the fall.

If you worry about the singularity and your longevity plan, and are a believer in Jesus Christ, I urge you not to worry–you have the real thing, the real longevity plan; only this plan is for eternity with our Creator and those we love, and not built on the hubris of human advancement that will surely perish.

If you are not a Christian, I urge you to check out the John Lennox lecture at my previous post. There is Hope. You don’t need to worry about whether you can afford the technologies of the Singularity, or about some ambiguous longevity plan about which the greatest minds have only limited belief based on conjecture. God created you and offers you eternal life through His death and resurrection–it’s a beautiful thing. Christ will restore your heart, will heal your body, will bring you joy.

Boris Groys On Art & A Christian Response

This is a very interesting interview with Art Historian and philosopher, Boris Groys. Here he claims that it is everyone’s responsibility to be an artist, which is, essentially, self-expression: to create oneself in one’s image.

However, as I’ve maintained in an earlier post, there must be something more to that, unless one thinks of ‘self-‘ as one’s authentic self. As a Christian, I believe that one finds one’s authentic self through the redemptive work in Christ, and the creative dance between oneself and God through the long and arduous process of repentance (or, in the Greek, ‘metanoia’.).

And it is on this point that I believe Groys’s statement to be correct (though he most likely would not agree with the context): That as human beings created by God, we are to seek out and live our true selves as our primary responsibility on this earth, and thus, as Groys maintains, become artists; but not creating ourselves in our own image, but rather being molded in the image of God, as we’ve been truly created.

This, however, does not mean that we become conformists to some kind of Christian gestalt particular to a denomination, but rather that as we live according to Christ’s redemption in our lives and thus become more of our selves, we become more truly and fully unique–as God created us. Hence, the life of art is not only to live authentically, but also to live in freedom–freedom to become truly ourselves.

And as much as Groys seeks to eliminate the soul from the definition of what art is, while still ironically seeking that which is ‘transcendent’, the Christian seeks to bring more of the work of the soul–that process of smithery–out into the materiality of his/her particular art.

Regardless of what one’s inherent beliefs might be, there are always things we can glean from the thought of others. In an article, titled “Immediations” from the The Research Journal of the Courtauld Institute of Art, Groys is posed a question about his suggestion that philosophers have a naturally closer relationship to art than do art historians, to which he makes this, to me, insightful reply:

We can look at art in two ways. First as if we were biologists trying to construct a neo-darwinian story of ‘our species’: how artists develop, how they succeed, failed, survived. In these things, art history is formulated like botany or biology. The second way of of considering art is part of the history of ideas. . . . So the question is whether we consider art history more like botany or more like the history of philosophy–and I tend more to the latter, because the driving force of art is philosophical (Vol I. No 4, 2007, pg. 4).

This explains how I became interested in art in general, and literature in particular. A friend of mine, who is now a professor of philosophy, once told me many years ago at the beginning of my philosophy studies at the University of Toronto that the best modern philosophers were found in literature. It took me a while to figure out what that meant, until I worked through and landed on some of my favourite 19th/20th Century writers (Joyce, Eliot, Dostoevsky, Beckett, Camus, name a few), and began working at fiction on my own.

What I draw from when writing is this history of ideas that I have been indoctrinated in, which as such remains a blessing and a curse: the former simply because new ideas and the dialectical approach to bringing numerous together and finding a new one, comes rather easily; the latter (namely a curse) because as a Christian writer, I find much of the history of ideas to be of a certain kind of citadel called ‘the history of reason or consciousness’ that I believe Christianity attempts to push us beyond–to very dramatically liberate us from. This requires a great deal of explanation, but I will say this of the matter: That in spite of all the talk of ‘soul’ and ‘reason’ and even ‘conscience’ one finds in philosophy, it will not teach you to love more, to become less self-centred, and, ultimately to give yourself to God. It may speak of those things, gloss over them, or bring them under some kind of straw-man judgment, but it will not give you love for God and your fellow human being. You may even read all the Kierkegaard you want, but, and he too would say this to you, it will not save your Soul–you must reach rock bottom and assent to God yourself. He will be there when you leap, but there’s no elevator, no automatic switch that you can simply intellectually dally with in your mind.

And what I attempt to write about is this very tension between the rational and salvific (I avoid using ‘absurd’ for those not versed in Kierkegaard and would thus interpret the connotation of that word as somehow subservient to reason), drawing out the existential struggle in pursuit of God within the overbearing ambiguity of existence itself. And the contexts I draw from are those closest to that history of ideas mentioned by Groys; those ideas held most dearly by the great thinkers whose works have shaped our western collective (un)consciousness.

Being a Christian Writer

Prefaces are about beginnings–and I have had, and continue to have, many of them. In the Christian life, our Way is made up of many false starts, detours, crash landings and stalled engines, all of which require some kind of re-entry into Life through the Grace of Christ, and some of which lead to the telling of one’s story–a way of prefacing the new life or beginning: “Well, things have been getting better these last couple of months, but you should’ve seen me a year ago at this time–man was my life a mess!”

For new books, I always read the Preface–it’s the best way to get inside the author’s head, or heart, and have a good thumbnail print of the work itself. One of my favourite prefaces is Schopenhauer’s The World As Will and Representation in which he suggests to the reader that if he or she doesn’t like the book, then it can be easily set upon a coffee table and used to hold a cup of tea (or something to that extent–the book’s not with me). So this blog is about prefaces, new beginnings, and the narratives that accompany and often precede them. Sometimes the ‘old life’ is simply one’s absence from church for a period of time spent gorging oneself on too many episodes of House MD in a row; however, there are other ‘old lives’ that are full of the rawness and grittiness of life itself–and those tend to be the stories I am interested in, both writing and reading about.

Are there Christians who seek out literature that draw the bow tautly between, as it were, the sacred and profane? Or, has fiction been bifurcated into a Christian stream that simply draws neat little parallels to scripture and blithely answers all of life’s questions, and, conversely, that of ‘secular’ fiction that enters into the funk of life, but with little in the way of redemption?

What does it mean to be a Christian artist anyway? I resonate with Tolstoy’s What is Art? in which he designates art as that which involves a struggle with the divine, with one or more transcendent topics that one must toil to get out; and it is in the toiling, the existential struggle, the dance with the Divine, that the product can be considered art. With this as my operative definition, I feel comfortable actually scrapping the ‘Christian’ and simply call such experiences ‘art’. Indeed, Merton talks about this as some kind of creative process: that as we give God our gifts (our writing, oration, visual art, etc) that He gives them back to us, and it is in this dance with God that we create. This creative process, this art, then, is the artist’s struggle with life, existence, despair, anxiety, guilt, and the redemption he or she finds in Christ.

What I want to know is if there are Christians out there who want to read such literature, and thus are not shaken or driven away by prose that is steeped in the funk of life; art that draws out the tension between the profanity of life and the redemption found in Christ.

If you are interested in this, please post me some feedback, whether you agree or think I’m way off.