Beauty will save the world.

–Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

Hannah Arendt & Leaving Planet Earth

“In 1957, an earth-born object made by man was launched into the universe . . .” so begins the Preface to Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition. “[An] event,” she continues, “second in importance to no other, not even the splitting of the atom.” For Arendt, the significance of the event was, as one journalist put it, “relief about the first step toward escape from man’s imprisonment to the earth,” which, Arendt concludes, unwittingly echos the line etched into the funeral obelisk of one of Russia’s great scientists: “Mankind will not remain bound to the earth forever.”

Hence for Arendt, at the heart of the satellite launch—and all subsequent travels to space and beyond—lies a deep sense of estrangement, of exile, that the eventual departure from earth somehow promises to remedy. Indeed, the launching of the satellite and subsequent landing of Apollo 11 on the moon in 1969, Arendt observes, point to a new epoch of modernity in which humanity not only rejects God, but also planet Earth itself—“the mother of all living creatures under the sky . . . the very quintessence of the human condition and earthly nature.”

And it is this rejection of the earth, of nature, that further heightens humanity’s estrangement from it. Today, this escape from the earth has become conventional through, for instance, high-profile private enterprises, such as SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, and Blue Origin—projects that seem to mark the height of human technical reason, but may indeed belie a deep rooted ennui.

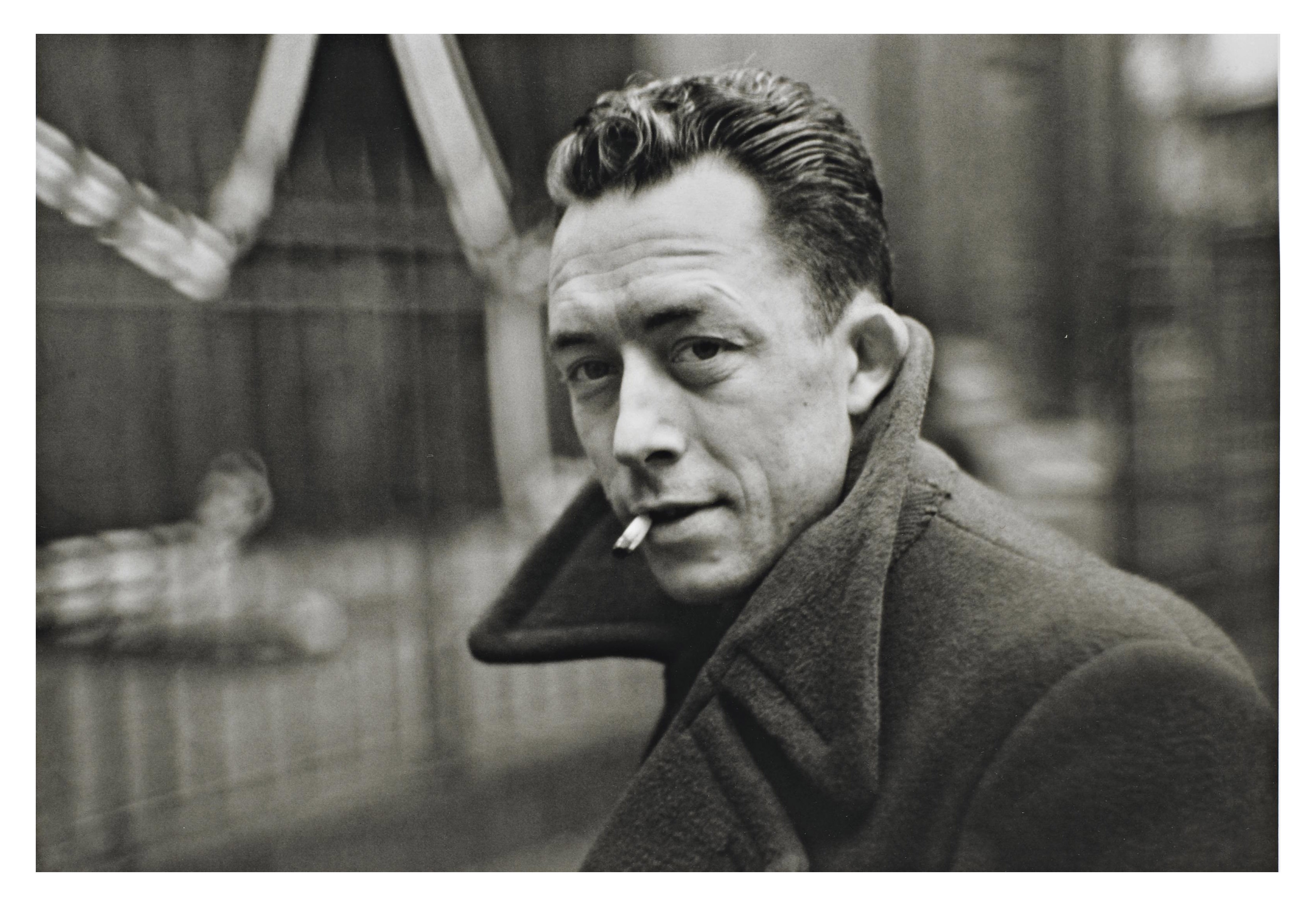

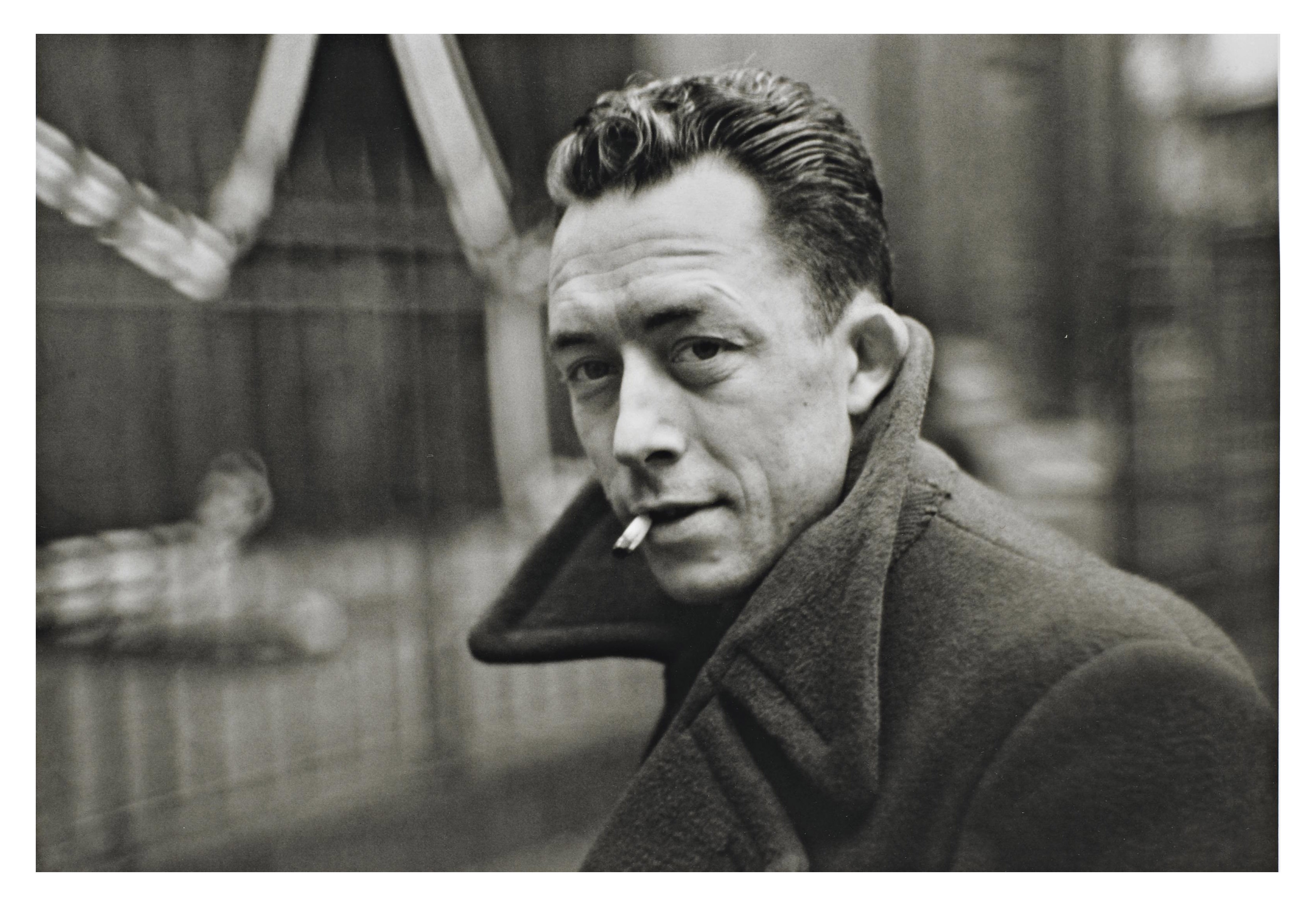

Camus and the Absurd

The Algerian philosopher Albert Camus observed that life is absurd. Absurdity was not something Camus preached as a way of life, or an objective or nihilist manifesto, but rather what he saw as a veritable tension within human existence itself vis a vis the natural world. Contrary to the 15th Century, we are no longer beings who naively accept the existence of a god, a world that is harmonious, a life that is inherently purposeful. Rather we find ourselves thrown into a world without form, without god, without order, without meaning. And this sense of estrangement to the world, of fallenness or thrown-ness (Heidegger), of absurdity, reached its culmination, its manifestation, through events that became (in the words of Derrida) its very paralysis: the use of human reason not to free humanity, but further subjugate it and ultimately annihilate it, whether through the gulags and gas chambers or the development of weapons of mass destruction. It was World War II and its holocausts that revealed the chimera of enlightenment, namely that human reason is inherently irrational. In modernity, human reason is turned back on itself thus exposing a world that is ultimately absurd. Whether it is a Nietzschean world of pure will or a Darwinian world of survival of the fittest, we find ourselves on a planet in which even our very creative freedom cannot escape its own will to power.

Existence Precedes Essence

That is why for modern philosophy, particularly the existentialists, existence precedes essence: I exist, and then I create who I am (my essence, my meaning, my identity, my destiny) out of it. In this way, I stand outside of the world and create myself over against it. The world does not posit me, rather I posit it. This modernist way of thinking came out of the radical skepticism of Descartes in which he famously concluded, “I think therefore I am”: my being proceeds from my thinking, not the other way around. Hence the thinking analyzing subject stands over against the world as object. It observes the world, it posits the world, it brings the world into existence out of its mind. The world, everything, is buffeted through the mind. Even God becomes a projection of one’s imagination, as claimed by the German Idealist and skeptic Ludwig Feuerbach.

How are we to deal with this world of absurdity? What ought we to do with a failed enlightenment project, when human reason is peeled back only to reveal pure absurdity? We go back to Arendt: we escape it, abscond for some higher star, to start over again.

Stanley Kubrick and Human Estrangement

And what better way to capture Camus, the absurd, and the rejection of and absconding from the natural world than through film. Today, there seems to be a flood of films about the future (indeed, the speed of technological time makes the future the new present), but Stanley Kubrik’s 2001 Space Odyssey remains one of the most iconic of that genre.

Kubrik’s Space Odyssey is a science fiction portrayal of the modern world, a world apprehended through the gaze of the subject, which necessarily establishes an inherent subject/object duality. It is the quintessential buffeted world—reality is projected through the mind, and thus the mind stands over against it. It is the height of human civilization, a world of spiralling space stations and technical reason. Even the monolith, that symbol of reason, is an abstract form—there’s nothing natural about it. It stands over against those who observe it. But in a world in which reason is turned back upon itself, the monolith thus becomes a symbol for something else: that same abstraction that Camus rejected as absurdity. Stanley Kubrik’s 2001 is thus a perfect depiction of the world of absurdity, a cosmic world that once was void, but now being formed in humanity’s own image. A solipsistic world in which the pod of space travel is a symbol of the solitary mind travelling through an otherwise meaningless void.

Hence the leitmotif of Kubrik’s film is not exploration or odyssey, but rather estrangement itself. If Homer’s iconic character Odysseus is the quintessence of journey—to venture out on a mission only to return home—then 2001 is anti-Odyssey: there is no homecoming, there is no destination but pure consciousness itself. Human beings are estranged from the earth, and from one another, which is represented in the scene when the astronaut talks to his daughter through a video call. Relationship with the other and with the world is existential and epistemological, i.e., largely egoistic and framed around technical knowledge, rather than ontological, related to being or that which is. There is very little hint of a world that exists outside the mind, that exists in and of itself.

The climax of the film reaches back to Camus’s absurdity: HAL9000. For by virtue of humanity creating the world in its own image, it creates its machines with the same existential make-up: fear, self-preservation, ego, will to power. Hence, HAL becomes an image of humanity: it seeks its own self-preservation over against the other. When Dave crosses HAL, he is driven out of the space ship and abandoned into the infinite void. The astronaut is treated as a means to HAL’s autonomous ends.

The movie concludes with a semblance of reassurance: that technical reason will win over absurdity, but in the end there is a tacit slipping back into absurdity, into estrangement. We see this in the final part of the movie, Infinity and Beyond, in which Dave ventures beyond space and time, he grows old, dies, and becomes pure consciousness—pure solipsistic reason without any real connection to being itself, without any connection to the other.

This conclusion of the film harks back to, or fulfills, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit in which Reason’s journey through human history becomes pure consciousness and thus, somehow, divine: the we that is I and the I that is we. A question remains: Is this Kubrik’s beatific vision or apocalyptic prophecy? And is there something supernatural driving the development of human reason, something that lies behind the veil of mere perception?

Andrei Tarkovsky & The Pursuit of Harmony

It is indeed this world of reason, this world of technical estrangement, that filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky wholly rejects in his films, particularly Solaris which to some extent is a direct critique of Kubrik’s 2001. In fact, Tarkovsky called 2001 “phoney on many points, and a lifeless schema with only pretensions to truth” Why? Because ultimately 2001 is a film estranged from the natural world, from being itself, from that which is (which may have been Kubrik’s point in the first place).

Tarkovsky’s view of the world and of art is shaped by his deep roots in Russian Orthodoxy. Russian Orthodoxy maintains a holistic ontology, meaning that nature and humanity are deeply interconnected through God who is everywhere filling all things. Reality is thus something that impinges itself on me, and is thus not a mere projection from my mind. It is a worldview antithetical to modernity. As such, Tarkovsky holds to a classical aesthetic stated, for example, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, namely that art is a mirror into nature, into being itself, into that which is, and not merely projected onto the world by the imagination.

One can see this in the opening scene of Solaris. While it is unequivocally a science fiction movie, the opening setting of Earth is that of immense natural beauty: rivers and streams, fulgent flowers, swaying trees, fish that swim, a galloping horse. Time stands still, almost as if in an eternal present—a technique Tarkovsky called “sculpting in time.” The length of scenes seems to play with a different kind of time horizon, namely kairos time—a creative, sacred, highly purposeful time—over against the chronos of modern technical society. The protagonist, a psychologist Kris Kelvin, is returning home. He is in a state of wonder as he stops at the river and splashes his hands through the water and gazes at the pondweeds that undulate to the current. Later, at his father’s house, he sits on the balcony and basks in the glory of a downpour of rain that soaks him to the bone. The scene represents the fullness of nature and humanity’s deep connection to it. The father’s house is also an icon of humanity’s interconnectedness to life, to meaning, to community. In the house are rooms with plants, a bee settling on partially eaten fruit—scenes from the Old Masters of painting, for Tarkovsky wanted to highlight and point back to timeless scenes of art prior to the rise of modernism and the paint splashes of abstraction.

In spite of the interconnectedness of humanity and nature at the opening of the film, however, there is a deep element of estrangement that broods over the middle scenes. Kris Kelvin is ordered to visit a space station circling the planet Solaris. Strange phenomena have been happening there. One astronaut was released from the space station after claiming to have seen a four-metre tall child on the surface of the water of Solaris. While initially glossed over as a mere hallucination, other members of the space station are having similar observations, hence the necessity for Kelvin to visit and report on what’s going on. But Kelvin is a scientist, a rationalist—“not some philosopher or poet,” he explains. He believes he is immune to absurdity, to any phenomenon that cannot be explained through science. However, when Kelvin visits the space station, he enters a world similar to Kubrik’s 2001: a place of technical reason and absurdity. In fact, the room where he stays strangely resembles that of Bowman’s room in 2001 in that phantasmagoric final scene.

Shortly after his arrival, Kelvin is inflicted with a series of hallucinations: his wife, who had committed suicide years prior, appears to him in a bizarre Nietzschean eternal recurrence of the same. She appears to him, then kills herself, only to reappear and kill herself again. Here is an existential moment of absurdity that Kelvin cannot apply scientific reasoning to. His wife’s appearance unshackles him and he finds himself in a struggle toward meaning, toward harmony, toward completeness. He does not try to push his wife away, but seeks unity with her under the risk of this absurd recurrence. Nevertheless, to fight the absurd, to push it back, Kelvin eventually leaves the technological, the place of estrangement, and returns home—to nature, harmony, and family. He approaches the house, and stares at his father through the window, then walks to the door. His father appears at the the doorstep. Kelvin walks up to his father, falls to his knees and clutches his father’s legs. The father receives his son by placing his hands on his shoulders in a brilliant representation of Rembrandt’s Prodigal Son—the son escaping the absurd and returning home to unity, harmony, and beauty.

Sisyphus and the Secular Age

Back to Camus. Existence is absurd because of the way humans have structured the world into bureaucracies, nation states, corporations, Facebook pages, and weapons of mass destruction. Jacques Ellul’s Technological Society provides a sociological language to Camus’s existential category of the absurd, namely ‘techne’ or technique—the never-ending striving for productivity and efficiency that demands faster and more complex systems. Nevertheless, these technical structures subjugate and estrange us from each other and the natural world, as we are seeing now, for instance, with the rise of AI. The technological world is thus a representation of estrangement; indeed, looking at Nick Bostrom’s book Superintelligence, technology very shortly will no longer need us, while we will be wholly dependent on it. For Camus, this apprehension of the technical world as estrangement, as absurd, when truly deeply realized leads to despair, and ultimately, when taken to its very end, suicide. But while Camus posits suicide as one way out of the world of absurdity, he is certainly not advocating it. For instance, the thesis of his book The Myth of Sisyphus is precisely that suicide, while one way of dealing with absurdity, is ultimately inadequate. The way to beat back the absurd is through the pursuit of meaning, and, ultimately, love and beauty, though Camus had a hard time fully understanding what that would mean. Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, in his book A Secular Age, critiques Camus (while applauding his struggle for meaning) that if life is absurd and thus meaningless, how does one go about asserting meaning? For Taylor, the struggle for meaning in Camus points to an a priori desire for the transcendent—something Camus was unwilling to consider or ascend to.

Beauty Will Save the World

One answer to Camus can be found in a Russian writer he deeply loved: Fyodor Dostoevsky. For in the Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky writes that it is beauty that will save the world; a beauty that connects one to nature, and fosters harmony with each other and a love for all things. When one confronts this beauty, one comes face to face with being itself, and one is transformed. This was the beauty that changed Dostoevsky when his life was suddenly spared while facing a firing squad–punishment for his part in a socialist revolutionary plot to assassinate the Tsar. When his life was spared, and he was sent into exile in Siberia, he immediately saw life as a gift from God, something to be lived fully with purpose and meaning. And this world of Dostoevsky, full of beauty and purpose and meaning, is Tarkovsky’s world too.

But to encounter this world of beauty, of meaning, and thus to beat back absurdity and despair, requires getting out of one’s head and opening oneself to being itself, to a world that is not a projection of the mind, but a world that is, that is deeply interconnected, that impinges itself upon us. A world to be loved, held, apprehended, and represented through unflagging creative endeavours. Like Tarkovsky shows in his films, beating back the absurd requires an orientation to the world that, contrary to our existence in the technological society that seeks to drive us beyond planet Earth, represents, indeed, a sort of homecoming.

Or as the great poet Czeslaw Milosz in his poem The Sun encourages fellow artists, “who want to paint the variegated world . . . ,”

Let him never look straight up at the sun

Or he will lose the memory of things he has seen.

Rather, in the final stanza,

Let him kneel down, lower his face to the grass,

And look at light reflected by the ground.

There he will find everything we have lost:

The stars and the roses, the dusks and the dawns.